- Title: A Clockwork Orange

- Author: Anthony Burgess

- # of Pages: 141

“What we were after was lashings of ultraviolence.”

In this nightmare vision of youth in revolt, fifteen-year-old Alex and his friends set out on a diabolical orgy

of robbery, rape, torture and murder. Alex is jailed for his teenage delinquency and the State tries to reform him – but at what cost?

Social prophecy? Black comedy? A study of free will? A Clockwork Orange is all of these. It is also a dazzling experiment in language, as Burgess creates “nadsat”, the teenage slang of a not-too-distant future.

There are quite a few movies I’ve watched purely so that I can stop avoiding the embarrassment of admitting I haven’t. Star Wars is one, Fight Club another. The problem with these kinds of movies is that you’re also not exactly allowed to dislike them. Or rather you are, but you’re clearly in the wrong.

I’d always lumped A Clockwork Orange in with this bunch, and with the additional prerequisite of needing to read the book first, it easily managed to get shoved off the list every year and into the next. It was only last month when I needed to choose a book to take on my visit home, with the single criterion of “as light as possible”, that I decided to give it a go.

At first glance, I couldn’t understand a word. In fact, had I nearly changed my mind about taking it, since I was worried I’d need a dictionary to make it through, and I obviously wasn’t going to have one available. However, a quick Google search made it clear that Google wasn’t going to be of much help either, and I was hooked.

Enough has been said and written (and argued and praised) about the horrific violence of Burgess’s cult classic. It’s not just horrific, it’s also astonishingly random, unjustified violence for the sake of violence. It’s gruesome and detailed and purely unpleasant. Unlike in Nabokov’s Lolita, where the criminal, albeit of a very different nature, soon has the reader empathizing with him, in A Clockwork Orange Alex’s crimes never elicit a feeling of sympathy, or at least that was the case for me. In that respect, it’s interesting to note how the cognitive freedom we associate with books, that let us “imagine beyond our wildest dreams” is also the same cognitive limitation that can protect us in instances like these. Whereas those watching Kubrick’s film would be forced to see these horrible scenes as intimately as their creator wanted them to, readers are protected by the limits of their own mind. Each rape scene was only as horrible as my mind would allow it to be, blurry and removed. I was protected by my imagination, which just refused to conjure up images that I didn’t want to see in detail, or that I didn’t have in detail to begin with. As for the movie, I’ve resolved not to see it.

Another aspect that helped distance the violence throws us back to my dictionary moment of crisis. The book, narrated by Alex, contains many words in a slang argot which Burgess invented especially for it. It’s called Nadsat, a mix of Russian and English, and at first, I simply couldn’t understand a word, so much so that in the first few pages I couldn’t even understand the horrors I was reading. The challenge of figuring out the language quickly captivated me. Burgess has said that he used Nadsat to keep the book from becoming dated, and make Alex’s voice ageless, but I think that by far the greatest result is how immersive the experience becomes for the reader, who needs to truly commit in order to be able to figure out the words and keep up. As I slowly picked it up, I began feeling like a member of some secret club, that I could understand Alex and that not anyone could. It was a story that required effort and dedication, which is not something I’ve come across very often. In fact, it turns out some versions of the book come with a key. Had I been Burgess, I would have had them banned.

As for the ending, well, I’m going to keep this review spoiler-free. We can leave that discussion for the comments, and in this case as well, all that can be said has been said by many others before me. The philosophical aspects of Alex’s reform go right over his head, and so unless you care enough about them, the narration style easily allows you to duck and have them blow right over yours too. It’s probably not the best stylistic choice on Burgess’s part since it makes the psychological and moral questions that could very easily be (and partially are) raised also very easy to ignore. To be quite frank, I didn’t find it very revolutionary either, in a world where conversion therapy is, unfortunately, alive and well. I was so utterly engrossed in the linguistic experience, that for that alone I’ve been recommending it ever since.

I’ve read many great books in my life, with better storylines, better characters, even better writing. But when was the last time a book demanded that I be fully engaged, even devoted, in order to be able to experience its story? I have no idea.

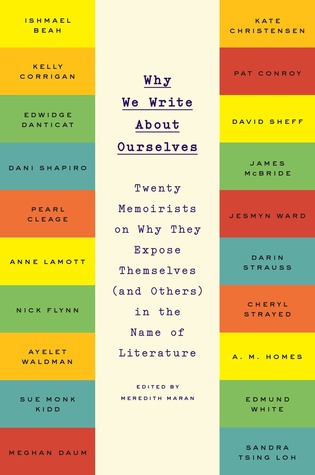

ouragement, and pithy, practical advice. Twenty of America’s bestselling memoirists share their innermost thoughts and hard-earned tips with veteran author Meredith Maran, revealing what drives them to tell their personal stories, and the nuts and bolts of how they do it. Speaking frankly about issues ranging from turning oneself into an authentic, compelling character to exposing hard truths, these successful authors disclose what keeps them going, what gets in their way, and what they love most—and least—about writing about themselves.

ouragement, and pithy, practical advice. Twenty of America’s bestselling memoirists share their innermost thoughts and hard-earned tips with veteran author Meredith Maran, revealing what drives them to tell their personal stories, and the nuts and bolts of how they do it. Speaking frankly about issues ranging from turning oneself into an authentic, compelling character to exposing hard truths, these successful authors disclose what keeps them going, what gets in their way, and what they love most—and least—about writing about themselves. he’s dropping into the lives of two teachers—and their love lost and found—in “Nine Inches”, documenting the unraveling of a dad at a Little League game in “The Smile on Happy Chang’s Face”, or gently marking the points of connection between an old woman and a benched high school football player in “Senior Season”, Perrotta writes with a sure sense of his characters and their secret longings.

he’s dropping into the lives of two teachers—and their love lost and found—in “Nine Inches”, documenting the unraveling of a dad at a Little League game in “The Smile on Happy Chang’s Face”, or gently marking the points of connection between an old woman and a benched high school football player in “Senior Season”, Perrotta writes with a sure sense of his characters and their secret longings.